By Justin Schwegel, Staff Attorney

Federal Covid-19 Unemployment Benefits and Eviction Moratorium.

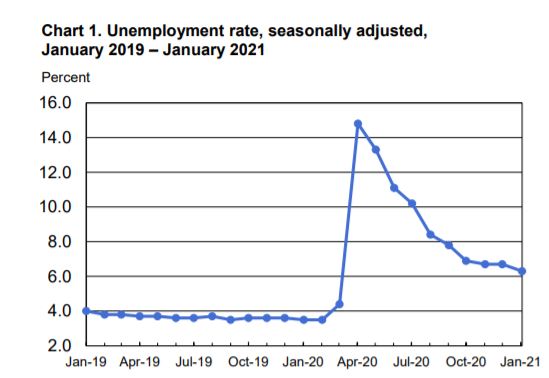

The Covid economic crisis created the worst unemployment crisis since the Great Depression. The unemployment increase in March 2020 was the worst since January 1975, with 1.4 million new claims. Congress responded, in part, with the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. It included an eviction moratorium and enhanced unemployment benefits. It provided federal unemployment benefits for those who had exhausted state benefits (Federal Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation under Section 2107) and for those, such as gig workers, who normally do not qualify for unemployment benefits (Pandemic Unemployment Assistance under Section 2102).

The CARES Act also provided a federal supplement to increase unemployment benefits by $600/week for those who lost work due to Covid-19 called Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC). This was a critical lifeline for many facing housing insecurity, as these funds paid rent and kept families in their homes.

In January 2020, Jasmine Pennington, from Philadelphia, had fallen one month behind on rent and reached an agreement with her landlord to make good on past due rent or she and her three daughters would surrender their home. She was working at a temp agency when Covid hit and she lost her job. Although she had almost caught up on rent (she was $50 behind by the end of July) the $600 FPUC supplement lapsed in July and she fell behind again. Her landlord refused to take part in a rental assistance program he deemed too administratively burdensome. A judge ruled that her agreement with the landlord fell outside the CDC eviction moratorium and Jasmine and her daughters lost their home.

Legislation with Gaps.

The FPUC supplement lasted from the passage of the CARES Act until July 31, 2020. On August 8th, President Trump issued an executive order authorizing FEMA to provide states funding to continue supplemental unemployment benefits, though federal funds would only provide a $300 weekly supplement to state benefits compared to $600 under the CARES Act. For Jasmine and her family, it was too little, too late.

The Trump executive order made the $300 unemployment supplement retroactive so that benefits could be paid for the week of August 1st, 2020 to avoid a lapse in supplemental benefits. The increased benefits it provided, called Lost Wages Assistance, was effected by directing FEMA to use $44 billion from the Disaster Relief Fund to pay states for the cost of providing supplemental benefits. The program lasted until funds were depleted on September 5, 2020.

In September, the House passed a bill that would have extended the $600 weekly federal unemployment supplement to January 31st, 2021. The same week, Senate leadership proposed extending the $300 weekly federal unemployment supplement through the end of December. Both parties agreed that extending federal supplemental unemployment benefits was necessary to avoid economic hardship but could not decide whether it should be $300 or $600.

Instead, for 16 weeks from September 6 until December 27 federal supplemental unemployment benefits lapsed and the supplement was zero. On December 27, President Trump signed an omnibus spending bill that reinstated the FPUC benefits at a rate of $300/week from December 27, 2020 to March 14, 2021. There was no money allocated to pay retroactive FPUC benefits to those unemployed from September 6, 2020 to December 26, 2020.

The eviction moratorium was renewed, and extended again by the CDC until March 31, 2021. This continues to keep millions of families in their homes. More targeted aid for those now living in pandemic-induced poverty, or more targeted rent forgiveness could change what will happen to these families after the moratorium expires.

Families Are Falling Behind.

The Covid crisis has exacerbated the national housing crisis. Millions are in the same boat as Jasmine. In December, credit rating agency Moody’s estimated that 12 million renters would owe an average of $5,850 in rent and utilities by January as a result of unemployment and lost income. The Aspen Institute estimated 30-40 million Americans (roughly 1 in 10) could face eviction, partially caused by a lapse in FPUC benefits. In Florida, an estimated 20% of renters are behind on payments. Millions have had to choose between eating and paying rent. Many homeowners are facing the same situation with missed mortgage payments.

Communities of color have been hit hardest deepening an already existing racial divide in housing insecurity. Black families were three times as likely (36%) as white families (12%) to be behind on rent; Latinx families were more than twice as likely (29%). Unemployment rates fell to 6.3% in January 2021, but this is still 175% the January 2020 rate, and black workers have been hit hardest.

$6,000 in Back Rent and Utilities Due.

The mechanism used to address the looming crisis is Economic Impact (stimulus) Payments. Past stimulus payments phased out beginning at $75,000 adjusted gross income (AGI) for individuals and $150,000 for married couples filing jointly. The most recent payment was $600, and the Biden Administration plans an additional $1,400. A $1,400 payment will not cure the deficiencies for the millions who owe on average nearly $6,000 in back rent and utilities.

The Biden Administration has shown an interest in targeting stimulus payments to those in the most dire financial straits. However, the targeting mechanism it has proposed is to limit stimulus payments to those with a lower AGI (based on 2019 data) rather than to provide more assistance to those most economically harmed by the pandemic.

Increasing benefits to those most in need of assistance through retroactive Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation for September to December would be successful to avoid pandemic-induced poverty and give families a way to pay back rent, compared to reducing benefits based on 2019 IRS AGI data.

Making FPUC benefits retroactive would also have the advantage of remedying policy that affected the amount of assistance people received because they were unemployed either too late or too soon. The legal patchwork governing federal pandemic unemployment compensation (the CARES Act, the August 8 executive order, the December 27 Omnibus legislation, and the Biden Administration’s proposed relief package) treats unemployed workers differently depending on when they lost their jobs. A worker who was unemployed in June 2020 due to Covid, but found work in July, received $2,400 in extra federal unemployment assistance. A worker who was unemployed in November due to Covid, but found work in December, received $0 in extra federal unemployment assistance. A worker who was unemployed in January 2021, but found work in February, received an extra $1,200 in federal unemployment assistance.

Making FPUC benefits retroactive for the 16-week lapse would provide targeted relief of $4,800, if based on $300 weekly payments, or $6,400 if based on $400 weekly payments as the Biden Administration proposed for future supplemental unemployment in its relief package. Retroactive payments of $6,400, in addition to broad-stimulus payments, would help most people who have fallen behind on rent and mortgage payments as a result of Covid-related unemployment avoid eviction and a pandemic poverty trap.

From the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Congressional Budgetary Office has not publicly released a cost estimate for retroactive FPUC benefits, but $44 billion allocated by FEMA provided $300/week of supplemental unemployment for five weeks in August when the national unemployment rate was 8.5%. This is a weekly cost of $8.8 billion. Unemployment rates for September (7.9%), October (6.9%), November (6.7%) and December 2020 (6.7%) imply that a $300 retroactive federal unemployment supplement would be much cheaper than the $8.8 billion/week of the FEMA program. The price tag would be well below $140 billion and assistance would go directly to those most impacted by the pandemic.

By comparison, the $1,200 direct payments provided in the CARES Act cost nearly $300 billion. $1,400 direct payments would cost more. Staving off the worst of the coming eviction crisis for under $140 billion dollars is a bargain. Considering homelessness costs $35,000-$40,000 per person annually, it is also a sound long-term investment for taxpayers.

I recently began working as a housing attorney for Gulfcoast Legal Services, a nonprofit providing free civil legal aid. My first client call was with a woman who fell behind on rent in January. She had lost her job and, when the federal unemployment supplement lapsed, she had burned through her savings to stay caught up on rent. Her lease expires in March and the eviction moratorium does not protect tenants facing eviction at the end of their leases.

Speaking to Marketplace, Diane Yentel of the National Low Income Housing Coalition warned, “An eviction moratorium on its own isn’t enough because eventually those moratoriums expire, and they create a financial cliff for renters to fall off of when back rent is owed, and they’re no more able to pay it then than they were at the beginning of the pandemic.” Retroactive FPUC benefits alone may not be sufficient to help all renters catch up on payments, but it would shrink the cliff their backs are up against and help landlords meet their own mortgage and maintenance obligations.